Grab your glass because today we are turning back the clock a bit to remind all of us of what human beings are capable of when they work together towards a common threat, act like grown-ups and leave the politics at the door.

Viva la Montreal! Not the city, although, if you haven’t been to Montreal. Get your tail feathers over there, because the city is fantastic. An old town kind of vibe mixed with an incredible food scene, Victorian architecture and wonderful romance of all things French.

What I’m talking about is the Montreal Protocol. An international treaty in 1987 to save the ozone layer that has actually worked and stood the test of time. The success of this treaty is not so much in the documentation and commitments themselves, but in the fact that the world actually followed through with it and we are seeing positive results in ozone protection.

Given it’s not discussed all that much, and given our enormous need to bring the world together to fight these climate and biodiversity crises at a time when it is so divided, we thought it would help to revisit this event and the results from it to remind us that humans are not always complete muffin stumps!

HOW THE PROTOCOL CAME ABOUT

The first generation of refrigerators were extremely toxic. Using chemicals such as ammonia as coolants, when they leaked in a home they could quite actually kill you! Thousands of people died in their homes every year in the early 1900s. These were not pleasant deaths either. These are burning your esophagus to the point of asphyxiation deaths. Not fun.

Then this guy Albert Einstein came long? Remember him? He and his lab partner build a fridge with no moving mechanical parts, thus no chance of leakage. However it was LOUD AF. And people decided they’d rather risk their own death than deal with a loud humming fridge, because, you know, people always have their priorities in order.

Another inventor named Thomas Midgley came along and invented chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs. Non-toxic coolants that instantly made fridges safe again. Or, safe for the first time. How lucky are we to have never lived through the era of homicidal fridges?

CFCs were hailed as a penicillin type of discovery. Not only did they solve the fridge problem, but they were adopted in of course air conditioning as well, hair spray, deodorant, paint, and more. Problem solved! End of story. What Montreal Protocol?

Oh right, well there was one issue with CFCs…..they just happened to destroy the ozone layer. In 1974, two scientists Frank Rowland and Mario Molina discovered that these CFCs were reaching our stratosphere, getting dissociated by UV rays, and releasing chlorine and bromine atoms that eat away at the ozone layer.

They were met with immediate resistance. The Chair of the Board of Dupont, a massive manufacturer of CFCs, said the report was a science fiction tale…a load of rubbish…utter nonsense. Because, you know, there is absolutely no conflict of interest there with Dupont. (Heavy eye roll). Many others denounced it as well, but as more scientists studied their research, it became undeniably true and quickly reached scientific consensus.

Something that was possible when a majority of us, ya know, believed in science.

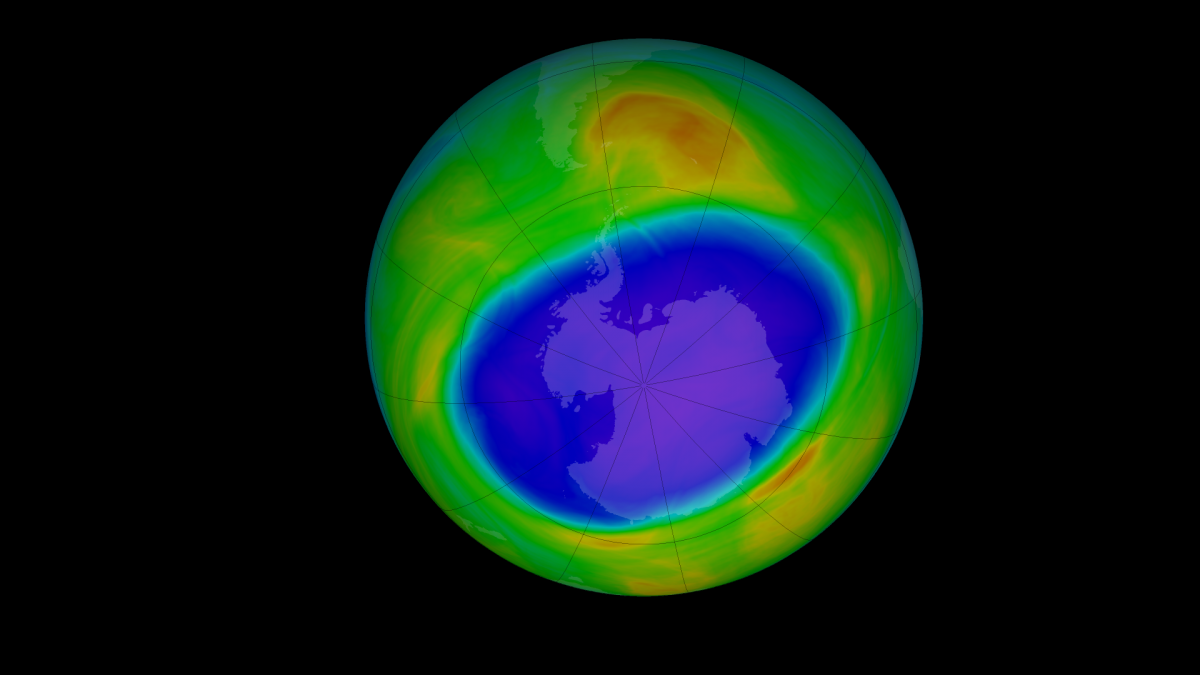

They noticed a particular hole over top of Antarctica. It would expand in the summer as wide as nearly 10 million square miles. That’s a big matzo ball. Why Antarctica? Well the incredibly cold winters there, the coldest on earth by far (much colder than the Arctic), would cause a special type of cloud to form that when mixed with the chemical atoms of CFCs would accelerate their damage. However the ozone was also thinning all over the planet.

This was a big problem, because the ozone blocks really critical UV rays. Without the ozone, humans would receive sunburn just walking around the block, skin cancer would become i’s own never ending pandemic, and the earth’s surface would get a lot warmer, as much as 0.4C warmer. Not good considering we are sitting at 1.1C warmer over pre-industrial levels and are desperately trying to avoid getting to 1.5C. A difference of…..wait for it…..ok that doesn’t really work in text…0.4C!

Scientists estimated that if CFCs continued their current expansion rates back then in the 70s, 50% of the ozone would be gone by 2050.

So the world took notice. In 1987, nations came together and signed the Montreal Protocol. Agreeing to phase out the most harmful of CFCs by 1996, other CFCs by 2010, and the less harmful but still toxic HCFCs by 2030. World leaders and their delegates were able to check their individual quarrels at the door and get this done.

SUCCESS???

You betcha. Big time. Yes, the world got together and solved a really important environmental problem.

Today the world has phased out 98% of ozone-depleting chemicals including 100% of CFCs. And while the ozone itself has many more decades to heal, you can see the size of the gaping hole has more or less stabilized since this protocol was put into place after years of acceleration, tying the end of CFCs to success with the ozone.

Now, CFCs were primarily replaced with HFCs (sorry about the acronym game here), which are ozone safe but it turns out act as greenhouse gases themselves. Hence, global warming. In October of 2016, the Montreal Protocol drafted the Kigali Amendment to phase out HFCs within 30 years. 110 countries have ratified that since, although the US is not one of them. I wonder why. Hmm….who became president of the US in 2016 and where did this president stand on environmental protection?

Nonetheless, this was a huge win. Not just because human adults got together and agreed on a treaty. That’s the easy part. A nice breakfast buffet and a well timed happy hour will get any grown man or woman to sign a few papers. More impressive is that we followed through with it. We prioritized the innovations needed to get off CFCs and we did it. The results followed.

We have not been able to do that with the Paris Accord, the agreement to phase out overall greenhouse gas emissions to net zero by 2050 in order to keep global warming below 1.5C drafted in 2015. Granted, the work needed to accomplish this such as transitioning from fossil fuels to renewables is a lot more complex and nuanced than new coolants for our refrigerators.

But that’s not really the point now is it? Because the challenge in our way and the reason every single country is behind their commitments made in the 2015 Accord has nothing to do with the technical hurdle to get there, but rather the politics and greed in the way. Incumbent companies that make a ton of money on the status quo and the politicians, let’s just be honest, they help place in office have no personal interest in changing things up. Again, whereas with CFCs we needed to change specific products; with net zero global emissions we will need to change super complex systems. These are not apples to apples.

So yeah, it’s harder. Still, it can be done. It must be done. We did it in Montreal. We have the ozone hold stabilized and on a path towards healing. We can do it with global warming as well.

Go raise a toast with your friends and family to Montreal. The city and the protocol. Share and forward this newsletter so people can be reminded that we are capable of good things, that we’ve done it before, and there is reason to believe we can do it again.

IN THE NEWS

Social Spiders Hunting in Packs

Sharing this story because a) spiders are awesome, and b) spiders are terrifying. What a great combination. This reminds me of when we realized velociraptors in Jurassic Park were able to coordinate and hunt in packs and their threat level went up 100 notches or so. This is just a great reminder of not only the intelligence scattered throughout the animal kingdom, but the social & interconnected nature of all life on this planet. Spiders have an incredibly valuable role as apex predators in their insect universe, consuming some 800 million tons of insects per year, keeping populations of many pests such as mosquitoes at bay. For context, humans eat about 400 million tons of fish per year.

Plastic Recycling gets Scientific Breakthrough

Recycling plastics today is an intensive and sometimes wasteful process. It’s very energy intensive and the quality of the material reduces each time. This is why many environmentalists have questioned the over-reliance on recycling in recent years in favor of moving faster to getting off plastics altogether. Well a new process uses zinc and methanol to break many common plastics down in just 20 minutes at room temperature. That’s big time progress. Still, we need to get ween off fossil fuel derived plastics as much as possible. There was a major intentional treaty signed this week to do just that which we’ll be breaking down in our next newsletter.

Europe’s Declaration on Russian Oil & Gas

As we detailed in our main story last week, Europe has a Russian problem on many fronts. Perhaps the most complex is their incredible reliance on Russian Natural Gas and Oil. 40% of their natural gas is from Russia and 25% of their oil. The EU got together in Versailles last week (side note, life is good to be part of any EU meeting as they take place in just incredible cities, start around 10am and end around 4pm with a 2-3 hour lunch break in between) and decide they need a plan to get off Russian dependency. They simply can’t just pull the plug as the US did, who gets just 3-4% of its oil from Russia for example. The results? Eh. No firm commitments on exact dates or firm sanction on Russia right now, but a plan is in place to get off Russia oil by 2030 and to replace it with renewables, which is great. Still a big question on the role nuclear will play, something Europe is very divided on (France captaining the pro-nuclear team and Germany the anti-nuclear team).

Are We Overdoing It with Tree Planting?

This is a really good piece from the NYT breaking down an issue we’ve been calling out for a while now. That smothering every open space we can with trees in the name of carbon offsets is becoming a huge problem. Yes trees are good. However, the market fury for selling offsets is leading to things such as creating sterile landscapes with widespread planing of single species, displacing local communities, worsening wildfires by filling natural fire breaks, and planting trees where they’ve never before grown which can kill local biodiversity and water supply. Forestation projects need to be carefully planned and highly targeted, not blanketed. And we really have to stop allowing projects that may have a net harm on the environment be used as offsets for larger corporations to leverage to basically avoid lowering their own emissions.

Well good news, fast forward to 2020 and that 19% has become 80%!. That’s right, thanks to the advancement in climate awareness and due to some fantastic work from organizations such as Climate Central, today over 80% and counting of meteorologists agree that human activity is driving climate change.

Climate Central has a division, aptly named Climate Matters, that distributes regular reports, graphics, videos and more from their climate science team to over 500 local news stations reaching over 90% of American media markets.

But do they see it as a problem? Well that seems still split 50/50. Of those that don’t see it as a major negative, it’s roughly split between half who are just not sure and half (25%) don’t see it as a crisis. So only slightly better than the overall US average.

This presents both a problem and an opportunity. The problem being that we need to get all meteorologists on board. The opportunity being as we do, we’ll be able to reach a lot more older Americans with a lot of voting power in maybe the only way possible.

You might think, why would a meteorologist, a weather scientist, not totally buy into the climate crisis? Well for one, there has always been some controversy over the role of climate change in specific storms. Meteorologists very fairly get frustrated when a social media post or CNN (yes they do this) goes out and blames the entirety of a hurricane on climate change. That’s not true. Hurricanes have been around for, well, forever. What is true is that they are growing wetter and more intense on average, due to warming temperatures allowing clouds to hold more water and warmer sea levels allowing them to pick up more steam as they race towards a coastline. But now, the baseline existence of the storm itself is not only due to climate change.

When it comes to things like heat waves, droughts, and wildfires, there is a bit more alignment across all of the meteorology community that global warming plays a role.

Another factor is personal political beliefs. Scientists are humans. Humans have beliefs. Humans have emotions. Emotions can trump reason. This happens to all of us. Those emotions can be magnified based on feedback. For example if you are a meteorologist in an area in the country where there is less public support for recognizing the climate crisis, you are likely to solicit negative responses.

Which is what makes this next video so dog garn inspiring. This meteorologist, Amber Sullins, has been sousing the horn for years on climate despite some of the hate mail she receives for it.

Sources for this story:

FALLING BEHIND ON ADAPTATION

Last week, the IPCC published the 2nd of 3 parts of their latest climate report, the 1st of which was published last August. While the report last fall provided a detailed look at where we sit when it comes to global warming and biodiversity collapse, the drivers, and the forecasts ahead, this report dug into the impacts on human communities & ecosystems.

One glaring hole revealed is that while we are putting a lot of effort and capital towards climate mitigation – mainly in the form of lowering emissions and investing in ways to capture and remove carbon – we are well behind investment we need in climate adaptation and resilience.

In terms of some definitions, adaptation is the process of adjusting our human systems and ways of life to the impacts and expected impacts of climate change. Investing in resilience is expanding our capacity to absorb and get through the impacts of climate change.

Of all the capital going into mitigation and adaptation globally, last year just 7% went towards adaptation and resilience, with the rest going towards mitigation. The United Nations Environment Program estimates that by 2030 we’ll need to spend $150-$300 billion per year on adaptation & resilience, and by 2050 this figure will be at $300-$500b. Yet the current global plan from COP26 last fall sees the top 50 developed nations spending just $50B in adaptation per year with no set plan currently for increasing it.

As many as 3.6 billion people live in areas currently highly vulnerable to climate change – half the planet! Yet even our most climate committed leaders and companies are not focusing nearly enough on helping these folks adapt for what lies ahead. And make no mistake, much of the changes coming are irreversible. So the need to adapt and become more resilient is unavoidable.

So why is that? And what are some examples of what adaptation investment looks like? And how can we solve this gap?

ADAPTATION EXAMPLES

Here are several examples of adaptation areas:

- Farmers shifting focus to more drought and heat resistant crops

- Increasing energy efficiency

- Improving flood protection via increased drainage infrastructure and insurance programs

- Prioritizing more localized consumption to lower the transportation needs of goods

- Preparing for increased rates of power outages with more shared touchpoint across our electrical grid with backup options to power our most critical infrastructure

- Investing in public health programs to prepare for increased disease spread from water and food borne illnesses

- Creating non-energy intensive ways to cool cities and buildings such as more green spaces and tree cover

- Social welfare programs and safety nets

There are also things that touch both adaptation and mitigation

- Regenerative farming

- Solar rooftops for working and middle class homes

- Shifting from cars to public transit and slowing down road expansion in developed areas

These all sound like good things right? And yes they are happening here and there, but not nearly at the rate of investment in mitigation. Again to the tune of just 7% of global investment compared to 93% for mitigation efforts. What’s driving this?

REASONS WE ARE BEHIND IN ADAPTATION

1. Lack of clear path to ROI

Perhaps the main reason, certainly the biggest reason for low adaptation & resilience investment from the private sector, which globally put just $500M into this area in 2021, is the lack of clear path to ROI compared to mitigation efforts. Take renewable energy. Investment in solar, wind, geothermal, and nuclear are booming. And this is great, we need them. However they also promise big time returns for investors, with a clear path in how to get there. Not so much for adaptation and resilience investment. This despite models in a World Bank Report that show for every $1 we spend on adaptation it creates $4 in net benefits. These net benefits however are built over time from many indirect ways. For example, adaptation efforts to invest in protecting river banks from sediment runoff due to degradation protects water quality over time which lowers health care costs and improves productivity over time. But the short term ROI is not as easy to capture.

2. Adaptation most needed in areas with less global economic power

The regions that need adaptation investment the most are South America, Southeast Asia, The Caribbean, and Sub-Saharan Africa. Yet most of the world’s economic power is in the US, Western Europe, and China. That’s a problem. Those countries are less inclined to invest because they want to take care of home first and foremost. Our economic powers, including the US, have no problem investing in extracting resources from these parts of the world, be it palm oil or cobalt, but they are hesitant to invest in protecting the livelihood of people in these parts of the world that desperately need it.

This is not only a problem globally, but regionally as well. For example, take the US. Heck take California. California is in a historic 10 year drought. Many smaller towns in central California are without reliable access to water because the state has failed to help these areas adapt. Meanwhile, massive investment has been put into drought adaptation for California’s massive agricultural industry and city centers such as Los Angeles, which is also due to there being a more direct path to ROI.

3. Lack of clear measurement

Mitigation is much easier to measure success against. Are we reducing the amount of emissions and net greenhouse gases or not? This is something we can measure fairly easily and all agree on globally. Adaptation and resilience investments are much harder to measure. This is because they have so many different inputs and variables, and typically have a much longer timeline to measure against. When we can’t easily measure things, we are less inclined to invest in them.

4. Lack of Climate Risk & Vulnerability Data

The IPCC report is a helpful look at where we are as a planet, and it includes some regional breakdown as well. However, individual countries, regions and towns do not invest in similar risk modeling and vulnerability data themselves. For example, we published a story earlier this year on how many cities across the United States are still working on flood forecasts based on models from the 60s and 70s because they’ve chosen simply not to spend the money to update them. Without rigorous investment from the government in modeling down to the local level, we are essentially flying a bit blind, and it’s hard to justify a long term investment in adaptation without a clear path to immediate ROI if you don’t have a model to support it.

The result? We are far behind where we should be in preparing our cities and communities and ecosystems for the climate changes to come. Increased droughts, wetter hurricanes, collapse of water systems, increased power outages, and so forth.

Not only that, but in some cases we are investing in the wrong areas of adaptation. For example:

a) Private companies are planting forests where forests have never been before, such as grassland ecosystems, in order to capitalize on the carbon offset market that wants to pay for those trees (ugh, how many ways can we hate carbon offsets?). This in turn actually leads more food insecurity, biodiversity loss, and displacement of local and/or pastoral communities. All in the name of wealthy person on Wall Street selling some offsets to company that then uses this to get out of lowering their own emissions.

b) 29% of our emissions in the US come from transportation. We love our cars. In order to drive them, we need roads, lots more of them. However studies have shown that increasing roadways doesn’t lower congestion long term, as we just fill that new space with more cars. Electric vehicle companies love this as they want to sell more cars and have a great climate story to tell when doing so. But these roads need a lot of carbon intensive asphalt and construction, lead to more cars of which even EVs have emissions of course in the electricity to power them, and tear up more natural land, such as building over wetlands that we need to absorb future flood waters. Instead we should be minimizing investment in more roads and cars, and maximizing and improving public transportation such as rail and buses.

OUR TAKE

It’s good to see all of the increased attention and investment the climate crisis and mitigation efforts are getting. It feels like we are on a legit path to getting off fossil fuels. Kinda. But we are not going to be able to mitigate our way out of really big changes already coming our way at this point no matter what we do going forward. We are going to get to that 1.5C warming mark or at least very close. No, scratch that. We are going to hit it. The numbers don’t lie. We can stay below 2.0C, as crossing that would get to a place where we start to lose some 20-30% of our coastal cities, but even then, changes are coming.

We have to invest in helping people adapt and be ready. As always, the problems for why we have not done this to date also point to the solutions.

- Develop viable, financially sustainable commercial models for investing in adaptation and the money will flow in. Governments should provide tax credits to the private sector willing to take on the risk here of less certain short-term ROI to further move the needle.

- We need to give ALL nations and communities and peoples representation at our global climate summits and pledges. The economic powers of the US, Western Europe and China should not be dictating the terms for everyone else just because of our outsized role in this fight to save the planet. We need to level the playing field when it comes to global cooperation. Yes we have the most economic power, but we’ve also caused the most damage since the Industrial Revolution as well. That to me sounds like they cross each other out, putting us at a net score of Zero. A small country like the Maldives that faces possible extinction likely scores positive on the climate front. Yet we call the shots and they follow along?

- Adaptation needs a better vehicle for measuring success along the way.

- National, regional, and local sectors need to invest in regular reporting and modeling via public-private partnerships with the same rigor the IPCC does in their global work.

This is all doable. Of course, it’s always doable. That’s the irony of this crisis we are in. There is no mystery of what needs to be done. We just have to do it.

Sources: